Watchmakers talk too easily of innovation. But this decade has seen unprecedented progress in movement manufacturing. Dubai Watch Week looks at where we’ve come these last 10 years

Back in the mid-2000s, Nicholas Hayek, the late founder and chairman of the Swatch Group, invited the Swiss competition commission to investigate him. It was, he said, unfair that through his network of companies, chiefly movement manufacturer ETA and hairspringprovider Nivarox, he had an industry monopoly.

This was no kamikaze mission. An archaic Swiss law meant that anyone who knocked on Hayek’s door and asked for movements and parts could expect to get them. Even his direct competitors.

Hayek had had enough. He was sick of keeping his competitors alive. ‘Why should I have to feed everyone else’s kids when I can barely feed my own?’, was the gist of his argument.

The great Swiss petri dish

Hayek, a brilliant mind, spun it both ways. His monopoly, he said, was stifling creativity and innovation. Changing the law would mean brands had to invest in movement manufacturing. They’d have to come up with their own ideas. To invent. And that, he said, would turn the industry into a thriving petri dish. Innovation, he said, was the key to the survival of Swiss watchmaking.

No one’s counting chickens, but it seems he wasn’t wrong.

In the years that followed, many of the big players outside the Swatch Group sank millions and millions of Swiss francs into movement manufacturing programmes. Breitling was reported to have spent five years and €20m ($22.4m at today’s rates) getting its debut chronograph movement to market in 2009.

With the commission snooping around Swatch Group and brands fearing a supply dead-end, a new era of movement creation began, and with it a new era of competition. This decade, brands have been queuing up to announce movements with bigger power reserves, greater resistance to the pernicious forces that destroy mechanical watches, and improved precision and reliability.

Power to the people

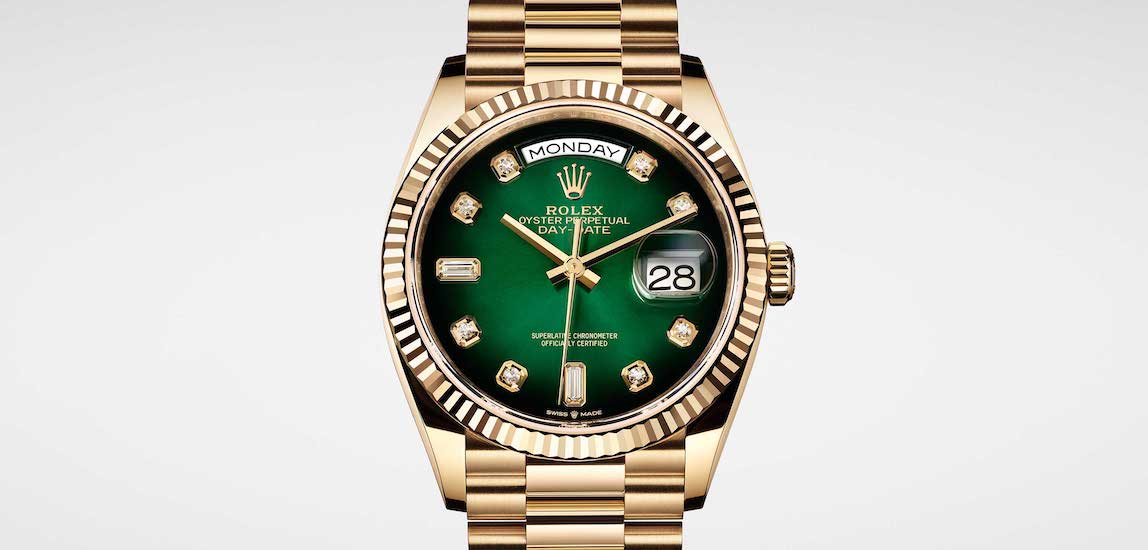

It used to be that a 50-hour power reserve was considered meaty. But now we’re seeing 70, 80-hour power reserves as a matter of course. Rolex, Tudor, Breitling, TAG Heuer, Panerai and a list of Swatch Group brands powered by a version of the Powermatic 80 are among a brand cohort making the three-day calibre normal.

Some went further. Patek Philippe was among the brands already pushing the envelope with 10-day power reserve watches, but such pieces came with a hefty price tag. Then in 2014, Oris unleashed an in-house calibre with a 10-day power reserve, sticking a sub €5,000 ($5,600) price tag on it. This year, Vacheron Constantin introduced the Twin-Beat system, which can extend a mechanical power reserve to an unprecedented 65 days.

A no-brainer?

Omega’s current generation of so-called Master Chronometer calibres make legion promises about resistance, the figure of antimagnetic resistance to 15,000 gauss being the headline. On launch, the brand famously claimed you could put a Master Chronometer in an MRI scanner and not expect to see a drop in performance.

And then just this month Jaeger-LeCoultre announced a new ‘care programme’. The grande dame of Le Sentier has been resting on its 1000-hour test as a guarantee of reliability, but it’s new package promises an eight-year warranty. Under the scheme, owners will be encouraged to bring a watch in for a check-up after five years, testing for magnetism, precision and water-resistance. If it fails on any of those fronts, Jaeger-LeCoultre will rectify the problem – under warranty.

Omega and Ulysse Nardin both offer five-year warranties these days. Rolex the same, with the addition of 10-year recommended service intervals on all its new watches, regardless of whether they carry one of its new generation calibres.

Would any of this have happened without Hayek’s outburst?

The promise brands make as we near the end of the decade is of Swiss watches that offer far greater mechanical variety to would-be buyers; increased user-friendliness; and greatly improved performance, reliability and durability.

Innovation and the future of the watch industry

Some might argue this is a boring kind of innovation, and in a way, it is. There’s nothing poster-boy about a watch that runs longer, not compared to say, the conceptual movements found in an Urwerk or the hyperbolic creations found in Harry Winston’s Opus series.

But it’s this kind of innovation that will underpin the industry for years to come. Watch buyers are more demanding than ever, and they’re being asked to pay more than ever for their watches. These gains matter if they’re going to be convinced to keep spending, therefore.

It may not be the legacy Mr Hayek will be remembered for first, but calling time on the old industry structure may yet prove to be one of his most significant contributions to the long-term health of the Swiss watch industry.